"Purchase discount shallaki on-line, muscle relaxant erectile dysfunction".

By: N. Norris, M.B.A., M.D.

Clinical Director, Albany Medical College

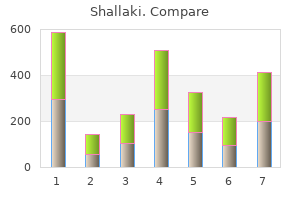

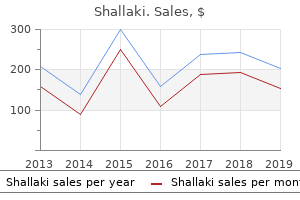

Alternative B muscle relaxant and alcohol purchase shallaki with paypal, Preferred Alternative: Trail Development Through Partnerships Heightened awareness of development opportunities from increased visitation might result in an expansion of retail trade and visitor services back spasms 24 weeks pregnant buy shallaki amex. The preferred alternative would cause minor spasms top of stomach order shallaki 60caps online, long-term beneficial muscle relaxant and anti inflammatory order shallaki cheap, and indirect effects because the majority of developers would be more cognizant of the impacts of their actions on trail resources. Agriculture has led to large areas being converted from wildlife habitat to croplands and/ or pastures of nonnative grasses. Timber harvesting for fuel or lumber has removed the extensive woodlands that covered the eastern sections of the trail, and livestock grazing has reduced animal densities in some areas and changed the composition of animal communities. Extensive residential, commercial, energy, and road-associated development have removed wildlife habitat. Natural resources on private lands could continue to be impacted by increased urban development and the construction of oil and gas pipelines. This alternative would result in minor, long-term, and adverse cumulative impacts on native fauna. Alternative A would have a minor, long-term, and indirect adverse impact on wildlife because there would be little awareness of the resources likely to be impacted. Cumulatively, the minor adverse effect of this action on native fauna would only incrementally add a minor degree of impact to the overall impact on natural resources. Alternative B, Preferred Alternative: Trail Development Through Partnerships Because of raised awareness about trail resources, it is possible that some property owners might choose not to initiate activities, such as development or land clearing, which might impact native wildlife. In such cases, the impact of this alternative would be local and beneficial to natural fauna. Heightened awareness of development opportunities from increased visitation might result in an expansion of retail trade and visitor services. The preferred alternative would cause minor, long-term beneficial, and indirect effects because the majority of developers would be more cognizant of the impacts of their actions on trail resources, such as wildlife habitat. Furthermore, any federal project resulting directly from the implementation of Alternative B would undergo sitespecific environmental analysis, and care would be taken to avoid and minimize impacts to these resources. Under Alternative A developing an interpretive program and appropriate visitor access, and installing trail signs would result in minor beneficial effects. Cumulatively, the minor beneficial effect of this alternative on the visitor experience would only add a minor degree of impact to the overall cumulative effect on the current visitor use and experience. Alternative B, Preferred Alternative: Trail Development Through Partnerships the high quality visitor experience that would result from the implementation of Alternative B is likely to foster widespread interest in the trail and its resources among a broader spectrum of society than exists at the time this document is being prepared. Other projects identified in the cumulative impact scenario, such as increase in heritage tourism and increase in websites, exhibits, and facilities that offer the opportunity to learn about and appreciate trail resources, would have minor beneficial impacts. The preferred alternative would cause moderate beneficial effects because a larger and more diverse audience would be able to learn about and appreciate trail resources. Cumulatively, the minor adverse effect of this action would only add a minor degree of impact to the overall cumulative effect on the visitor experience and would result in moderate, long-term beneficial and indirect impacts. However, at the time this document is being prepared, the planning team is not aware of any specific project that would have an overall negative effect on landownership and use along the trail. Although the participation of landowners would be voluntary, it is likely that the trail designation would raise awareness of issues associated with the impact of incompatible land uses on the trail. No additional impacts on landownership and use would result from the implementation of this alternative. Alternative B, Preferred Alternative: Trail Development Through Partnerships Although increased urban development would not necessarily decline due to the trail designation, greater awareness of trail resources might result in less detectable changes in land use. The same would be true for other forms of development described in the cumulative impact scenario. Alternative B would encourage more interest in the protection of resources along the trail, which could entail changes in land use and development trends. The trends identified under the cumulative impacts scenario have the potential to impact land use along the trail. However, at the time this plan is being prepared there are no specific development projects being considered that would have major impacts on landownership and use. Alternative B would result in moderate, beneficial, and indirect cumulative impacts on landownership and use along the trail. At this time it is not possible to speculate on the overall cumulative effect that these projects would have on such conditions. Some minor socioeconomic benefits are likely to result from trail development activities, increased visitation, and government expenditures associated with the development of this alternative. Alternative B, Preferred Alternative: Trail Development Through Partnerships Several projects identified in the cumulative impact scenario have the potential to impact socioeconomic conditions along the trail.

Presidial troops had been partially replaced by the Second Free Company of Catalonian Volunteers muscle relaxant bath buy generic shallaki 60 caps on line, whose Commander was Lt Col Pedro Fages spasms upper left quadrant buy 60caps shallaki with mastercard. Some of the soldiers who served later at Las Nutrias or in other places are listed in Chapter 9B muscle relaxant xanax generic 60 caps shallaki visa, below muscle relaxant vs analgesic purchase generic shallaki pills. It was likely late 1779 or early 1780 before the news reached Sonora and subsequently Alt~ Pimeria. The overland passage from Sonora to California had one critical area, the Colorado River crossing, which was controlled by the friendly Yuma Indians. In order to consolidate the ties of the Yumas to the Spanish, Anza proposed that a Presidio be established at the crossing area, with the usual supporting missions. This was finally carried out in 1779 and 1780, but the settlers arrived too late to plant crops and became a burden to the Yumas and their food supplies. The Seri Indians of the mountains of Sonora, never friendly with the Spanish, rose up in rebellion and had to be put down. They were overpowered by a force wlfich includM the Catalonian Volunteers under Lt Col Pedro Fages. It thus happened that this force w ~ available in the area when it was learned that the Yumas had also revolted. News of this request probably reached Sonora in 1781 and was acted on in August, 1781. Commandante-General Felipe de Neve had stopped the contributions in New Mexico in April, 1784, soon after he knew the war was over. The collections later made in Sonora were likely those of promises made at the time of first solicitation. As in California, the amounts contributed are known, but the names of individual contributors have not been found. During this period of time, New Mexico has jurisdiction over what is now N o r t h ~ Arizona, as it had long had contact with the Moqul (Hopi) and Navajo tribes. The Moquls had rejected the Spanish ever since the 1680 uprising, but in 1780, they were starving from the severe drought. Lt Col Anza believed he could get them to accept Spanish rule and he led an expedition into their country in late 1780. He was able to get some to return with him to New Mexico to survive, but most refused. They were so decimated from the drought that they were never again a threat to the Spanish. The names of the soldiers and militia who participated in this expedition have not all been recovered. Anza led ~n expedition from New Mexico to Tucson, establishing that a trade route was feasible. He was joined in this exploration by contir~gents from Sonora and from Nueva Vizcaya. New Mexico could now envisage trade with California along the new trails being developed. Part of the strategic plan for securing Alta California was to establish another Presidio at Santa B~bara, establish Channel missions, and esta~. The Expedition for these objectives was headed by Captain Rivera and was in two parts. The first part crossed from San Bias to Baja California, then moved up the peninsula to Mission San Jose. The second part moved north from Sinaloa through Sonora to the Colorado, which it reached in June, 1781. The families from this group were sent on to San Jos~, while Capt Rivera and several soldiers stayed with the livestock at the Colorado, allowing them to fatten up on the beans and other supplies the Yttmas depended on for winter sustenance. In July, 1781, the Yumas rose up in rebellion and killed all ",~hepriests and most of the soldiers and male settlers of the mission settlements. Rivera and his contingent of soldiers, capturing all of the livestock intended for California. The first campaign by Lt Col Pedro Fages was able to contact the Yumas and ransom most of the captive wives and children. They were not able to subdue the Yumas, so Lt Col Fages was sent to California to gain help. By the time he arrived in California, the Colorado River was in flood stage and the campaign had to walt until Fall, 1782.

They provide clues to the locations of the routes as they may be found on modern landscapes spasms near heart cheap shallaki master card. Such research and publications can help clarify the locations of various segments muscle relaxant zolpidem discount shallaki american express, and improve our general understanding of El Camino Real de los Tejas National Historic Trail and its varying routes through time and across the landscape muscle relaxant for alcoholism cheap shallaki 60 caps without a prescription. Several reports and publications summarizing various aspects of trail history exist muscle relaxant non-prescription order 60 caps shallaki, but there has been no comprehensive effort to collect all of the data in one place. Often, data are found in unpublished sources, such as the notes of researchers, for which the original source data is not known. The planning team recognizes that a handful of researchers have spent decades investigating trailrelated cultural resources, and that this research will probably be ongoing for decades. As mentioned above, during the course of preparing this plan, the planning team made a strong effort to summarize and organize all data into a comprehensive database that can be easily accessed for research purposes and expanded and updated. An analysis of the geographic distribution of historic resources along El Camino Real de los Tejas National Historic Trail suggests some interesting patterns. While some counties had no trail-related sites previously recorded, other counties had dozens of potential trail-related sites for which studies were readily available. For example, more than 70 Spanish Colonial and historic American Indian sites were recorded for Bexar County. The inventory of trail-related resources focused primarily on previously recorded sites. It was not an exhaustive search for all possible resources; therefore, it represents only a sampling of the total number of potential resources. This sample is neither systematic nor random, and it is heavily skewed by the fact that some areas have been studied intensively by historians and archeologists, while others have not. As a general rule, more professional studies have been conducted in counties where Page89 c haptEr 3: a ffEctEd E nvironmEnt major settlements, such as missions and presidios, are known to exist and more is known about resources in these counties. Trail Segments Retaining Physical Integrity In some places, physical evidence of the trail has been obliterated or obscured by development and other man-made changes in the landscape, such as agricultural activities or tree harvesting; however, numerous original segments still survive and anyone with a small amount of training in landscape surveying should be able to follow them. In those cases where the depressions cannot be explained by natural processes such as erosion or by modern farming, hunting, logging, or forest management activities, and if the depressions remain consistent in width, the depressions could be the result of the natural wearing of carts, wagons, oxen, or foot traffic-in other words, they could be remaining traces of the trail. Archeological research would then be necessary to associate the trace, rut or swales with a period of time when the trail was in use. Researchers have identified intact trail segments in Bexar, Houston and Sabine counties and in Natchitoches Parish. Segments in Brazos, Karnes, Nacogdoches, Robertson, San Augustine, and Wilson counties have been physically identified, but their relationship to the period of significance for the trail has not yet been confirmed. Some segments of the original trail have been upgraded into modern dirt roads; in some cases, they have been paved. It roughly follows the original route used by traffic crossing the Sabine River before 1822, when Fort Jesup was established and El Camino Real de los Tejas alignment was no longer the only route from Texas to Natchitoches. Others, like Ormigas Road, the Texas Star Road, and the Camino Carretera have been upgraded Page90 to allow for modern travel, but they still retain a considerable integrity of setting. In some of these "pass-through" counties, documentation of resources was often accidental. During the Spanish Colonial period, travelers mostly crossed the river at fords that were, by definition, shallow and did not require a ferry or bridge structure. However, some places where travelers crossed the river were deep enough to require simple bridge structures, such as fallen trees that were laid across the river, and there are occasional references to the use of rafts along the trail, indicating deepwater crossings. It has been documented that people made river crossings at each of the dams serving the five missions in Bexar County. It is clear that, although favored places to cross the river were typically undeveloped fords, deeper waters in other areas may have necessitated man-made structures to accomplish the river crossing. While most maps show trails intersecting at roughly perpendicular angles to rivers, crossing the river using a ford often required following a river for some distance away from the main trail, locating the ford and using it to cross the river, then traveling back to the main trail, a fact corroborated by travel narratives. The location of fords along the trail is important in trail documentation because such locations help in mapping trail routes. Furthermore, parajes were located next to many places where river crossings were made and can provide clues to life on the trail. In a previous study of trail routes (McGraw et al 1991), dozens of fords and river crossing places were recorded. Many of these were Chapter 3: Affected Environment - Previous Research confirmed by the use of a combination of aerial photography and field investigations. Most parajes along the trail were simple campsites, usually located near river and creek crossing places, where travelers could find good water near the trail.

We extended this analysis to find the pattern of distributed brain activity that was most prevalent in one subject group and least prevalent in the other (Friston muscle relaxant glaucoma buy discount shallaki 60 caps on line, 1997; Friston & Frith muscle relaxant triazolam purchase 60caps shallaki overnight delivery, 1995) spasms quadriplegia purchase shallaki american express. As such muscle relaxant safe in breastfeeding purchase shallaki without a prescription, the functional network is normal, but is simply differentially active in the two study groups. This finding is important because it suggests that, at least for this episodic memory functional network, the basic structure is intact. In retrospect, the functional activation that we observed, especially in the eight-word recall condition, was more related to the retrieval aspects of the task than to encoding. In addition, the dorsal parietal and prefrontal circuit that was identified seems to suggest a high degree of attentional load, even though the task was auditory (and that loop is usually associated with visual attention) (Posner & Petersen, 1990). Thus, consistent with the growing body of neuropsychological, behavioral, neurological and neuroimaging data, the loss of semantic knowledge may be peculiar to those pathological states that affect the functional integrity of the temporal lobes (Hodges & Patterson, 1995; Hodges et al. Structural and functional imaging studies demonstrate that these conditions are associated with severe disruption of the function of the language-dominant temporal lobe (Mummery et al. As noted by Perry & Hodges (1996), there is considerable variability in the nature and extent of semantic memory dysfunction, especially early in the course of the dementia (Hodges & Patterson, 1995), and there is evidence to support models that differentially emphasize storage loss, retrieval defects and alterations in the basic structure of semantic memory (Bayles et al. Although the first of these potential mechanisms would involve a deficit in semantic knowledge, the latter two would represent situations in which a failure on a "semantic" test would result from limitations in nonsemantic cognitive operations necessary for the appropriate use of an intact semantic knowledge base. They also have a great deal of difficulty recognizing the name of a pictured object in a multiple-choice task when the distractors are drawn from the same category as the target object, but not when they are drawn from other categories (Chertkow et al. This pattern of performance may reflect a preservation of category information, coupled with a loss of those specific attributes that make it possible to differentiate semantically related objects-hence the confusion with other items from the same category. Demented patients can be quite accurate (95% correct) when asked to recognize features that were attributes of a target (Grober et al. These studies used a variety of latent structure techniques, including multidimensional scaling, to analyze the organization of information in semantic memory. In addition, relationships among the stimuli along the multidimensional axes also differed between the patients and controls. Nebes (1992) has argued that one possible source for this discrepancy lies in the differing cognitive demands imposed by the experimental tasks. While not minimizing the nonsemantic processing demands of individual tasks, consistent findings across several tasks would point toward a degradation of semantic knowledge. Indeed, their data demonstrate a high reliability between tests (and within items). This may reflect, in part, the multifactorial aspects of semantic memory, and may also reflect the fact that various aspects of semantic memory function are subsumed in different neuroanatomical regions. The heterogeneity of symptoms and symptom clusters may reflect both cognitive and pathological variation. For our studies, the focus is on the grey matter and these images are smoothed (using a 3-D Gaussian filter) and analyzed using a between-group analysis to identify the voxels with significant differences in intensity, reflecting differences in brain volumes (see also Sowell et al. The left-hand image shows the cortical atrophy in the languagedominant left hemisphere, with the typical temporoparietal gray matter loss. The right-hand image shows a view in the coronal plane, demonstrating the tissue loss in the inferior temporal lobe and hippocampus. There were no significant differences between groups in education or on overall cognitive impairment, but the groups did differ significantly on age. The analysis revealed a significant difference in the gray matter volume of several temporal lobe structures. In addition, middle inferior regions of the temporal lobe, the fusiform gyrus and parahippocampal gyrus, also had significant differences in density between groups, such that the patients with poor naming had reduced volumes relative to those with good naming. These structural data are consistent with the existing functional neuroimaging and neuropsychological studies that have demonstrated the critical role of the temporal lobe in the processes needed to execute semantic memory tasks. There is reliable functional activation of the left temporal lobe during object-naming tasks (Martin et al. However, a functional neuroimaging analysis of a semantic task revealed activity in the left posterior inferior temporal gyrus, and they suggested that the decreased functional activation found in these patients was due to lack of input from the atrophied anterior temporal lobe to the posterior inferior temporal gyrus, and not due to atrophy of the posterior inferior temporal gyrus. Thus, while there appears to be a common final pathway to explain the naming defect, the cause of that defect differs between diseases.

Buy shallaki 60 caps lowest price. Best psoas muscle trigger point stretch - iliopsoas muscle release - hip flexor stretch.

Don Jose de Galvez y la Com~dancia General de las Provincias Intemas del Norte de Nueva Espana infantile spasms 8 month old purchase cheapest shallaki. Sevilla spasms pronunciation generic 60 caps shallaki mastercard, Spain: Publicaeiones de la Escuela de Studios Hispano-Amerieanos de Sevilla ql spasms purchase shallaki with mastercard, 1964 spasms vitamin deficiency buy generic shallaki. There were more abandoned Jesuit missions than new ones established by other or6ers. When the Jesuits were expelled in 1767, the Franciscans took over, with the Dominicans replacing Franciscans in Baja California in 1769. The Missions were established n~ar existing Indian rancheriast or at places where agriculture and self-sufficiency were possible. The idea was that in ten years, the Indians could be converted to Christianity and settled into village farming near the missions. This did not work out very well, and some Indian groups were not fully converted after 100 years. What did happen is that European diseases were introduced, and the Indian population died away. Smallpox was one of the most effective killers of Indians, and thcdndians of Texas rancherias made a direct connection of smallpox to the appearance of the blackrobed Jesuits. When the Jesuits baptized Indian children, the parents expected them to die of smallp6x. What the Indians were unable to do under the missions was to move away tc Meaner areas and new food sources as they had traditionally done. When the Indians died out or moved away in fear, more and more Mexicans took over the land near the missions. Another gradual transition was the use of Spanishsounding names by the Hispanicized Indians. In no case could he read and write, so the record is how others perceived his social status. Now this does create a problem for genealogists trying to sort out church records or family traditions. Another confusing factor is that SpapJsh families who were members of the church were obligated to sponsor Indian neophytes and the children of neophytes in birth, marriage and confirmation. This estabSshed lasting relationships between some Spmfish and Indian families, ~Mth Indian children taking the names of their sponsors or living with their sponsors if their own parents died. What the missions did best was to introduce the Indians to new crops, livestock, and new ways of thinking about making a living. They weaned the Indians away from traditional hunting and gathering into dependence on year-round agriculture and living in one given area near the missions. So, Indians who left their missions were hunted down by the Presidial soldiers and returned, where they were punished by the soldiers, as directed by the priests. When the missions were secularized, the Indians lost out to the Spanish or Mexicans. In general, this happened in the nineteenth century; but taking over the best Indian land was a common practice in all Border areas from the beginning, whether by the missions, presidios, or ranchers protected by the presidios. The operating missions and visitas in the 1779-1783 time era included: Baja California(under Dominicans): San Jose del Cabo, Santiago de los Coras, San Francisco Javier/SanPablo, Comonda/San Jose, Purisima Concepciotl;Mulcge/Santa Rosalia,Guadalupe, San Ignacio,Santa Gertrudis,San Francisco de Borja, San Fernando de Vclicata,Rosario, Santo Domingo, and San Vicente Ferrer. Alta California (under Franciscans from Queretaro): San Diego, San Carlos, San Gabriel, San Antonio, San Juan Capistrano, San Luis Obispo, Santa Clara, and San Francisco. On the Rio Altar in Sonora were San Ignacio de Caborca, San Diego del Pitiquito, Altar, San Antonio de Oquitoa, Atil, Santa Teresa, San Pedro y San Pablo de Tubutama, Saric, Busanic, Tucubavia, Arizonac, and Planchas de Plata. On the Rio Magdalena in Sonora were Santa Arm, Magdalena, San Ignacio de Cab0rica, Imuris, and Nuestra S~Eora de Concepcion de Caborca, and Nuestra Senora Guadalupe de Cocospera. The two missions on the Colorado, La Purisima Concepcion and San Pedro y San Pablo, were also under jurisdictior~ of the Sonoran Franciscans. New Mexico (under Franciscans from Queretaro): the missions upstream from Santa Fe were Tesuque, Nambe, Pojoaque, San Ildefonso, Santa Cruz de la Canada, San Juan, Picuries, San Jeronimo de Taos, Santa Clara (west of river), Albiquiu (west of River). Those downstream from Santa Fe were Santo Domingo, Sandia, Albuquerque, Cochiti, San Felipe, Santa Aria, Zia, Jemez, Laguna, Acoma, Zuni, Isleta, Pecos, and Galisteo.